By Siena Watson

Figure 1: Porcelain crab in finger bowl (Image credit: Siena Watson)

In our second Arthropod lab, we got to look at many marine species, including crabs, shrimp, and barnacles. Organisms within Phylum Arthropoda share certain traits, including an exoskeleton that they periodically molt and jointed appendages that are specialized in each region of the body. These sections of the body, called tagmata, have provided the basis for specialization of their associated appendages and have allowed for the large diversity of arthropods that live in many different habitats. This specialization of appendages is what drew me to look at the porcelain crab in lab. Petrolisthes cinctipes, also known as the Blue Porcelain Crab, is an arthropod and is part of the infraorder Anomura, which also includes hermit crabs. In lab, I found two interesting specialized structures of the porcelain crab and wondered what their functions were.

Figure 2: Sketch of porcelain crab indicating location of grooming limbs and “sponges” (Image credit: Siena Watson)

The first was the sponge or loofa-like structure on each of the two front claws. Given that they are facing the head of the crab and the feathery fan-like structures that they use to feed, my best guess was that these “sponges” could be used for cleaning off food or parasites from the mouth parts and fan- like feeding structures. However, in my search to find out what these ‘sponges’ were, I found a paper that described the observation of another porcelain crab species, Petrolisthes cabrilloi, using these structures, which are actually tufts of setae, to feed. After a layer of detritus built up on top of the substrate, a few of these crabs were observed extending their claws and scraping the tufts across the substrate towards their body, gathering detritus on the setae. The crab would remove the detritus from each tuft with its mouthparts (1st and 2nd maxillipeds) and appeared to consume the detritus (Gabaldon 1979). However, this method of feeding was not observed when the layer of detritus was absent. This kind of feeding could be an alternative to their usual filter feeding when conditions are unfavorable, such as during increased turbidity or competition with other filter-feeders (Gabaldon 1979).

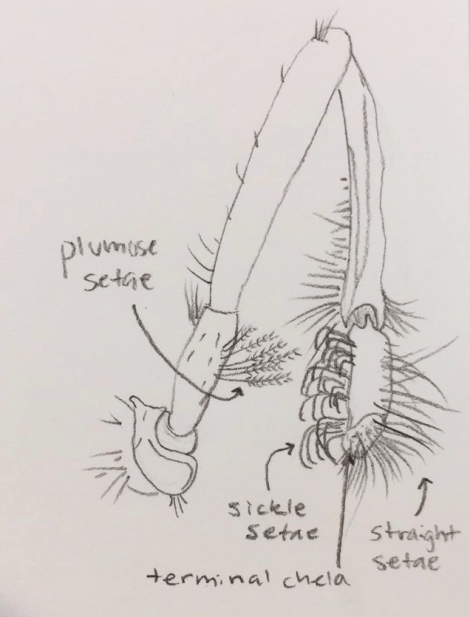

Figure 3: Sketch of grooming limb (5th periopod) of porcelain crab (Image credit: Siena Watson)

The second structure that caught my eye was the small leg, or pereiopod, positioned on top of each side of the carapace. This fifth pair of pereiopods is usually a walking leg in true crabs, but is modified into a grooming limb in the porcelain crab. In fact, the grooming limb is a synapomorphy among the Anomura (Fleischer et al. 1992). The grooming limb is very effective at preventing parasitism as it can reach most of the body and the gills to remove parasites. Each limb can even reach into the gill chamber of the opposite side, so if one of the grooming limbs is lost, the other is still able to keep both gills free of epibionts and debris (Fleischer 1992). The grooming limb is armed with multiple kinds of setae, sensilla, and a toothed chela, each of which have an important function in grooming (Fleischer et al. 1992). The straight setae can reach deep between the gill filaments and sickle-shaped setae help reach otherwise inaccessible surfaces of the gills (Fleischer et al. 1992). The sensilla likely include the plumose setae at the base of the grooming limb to help it identify if there are fouling objects present and the club-shaped setae and smooth setae around the toothed chela likely are chemoreceptors that help it distinguish between parasites and other fouling epibionts.

Figure 4: Photo of terminal toothed chela of 5th periopod of Petrolisthes cinctipes using scanning electron microscopy (TP: tooth processes, SS: smooth setae, PS peripheral setae) (Image credit: Fleischer et al. 1992)

The toothed terminal chela of the grooming limb is extremely important for maintaining the reproductive ability of the crab, as it helps in the removal of firmly attached rhizocephalan cyprids, the larvae of a derived parasitic barnacle. These parasitic barnacles sterilize the infected crab for life, effectively preventing it from reproducing. Although these structures at first seemed arbitrary, they both have an important function, whether it is providing the crab with an alternate way of collecting food or helping the crab prevent itself from becoming sterile. Next time you discover an interesting invertebrate structure, research its function! You may find that it is more important than you thought.

References

Fleischer, Johan, et al. (1992). “Morphology of grooming limbs in species of Petrolisthes and Pachycheles (Crustacea: Decapoda: Anomura: Porcellanidae): a scanning electron microscopy study.” Marine Biology 113.3 425-435.

Gabaldon, D. J. (1979). Observation of a possible alternate mode of feeding in a porcellanid crab (Petrolisthes cabrilloi Glassell, 1945)(Decapoda, Anomura). Crustaceana, 36(1), 110-112.